The Neurological Toll of War on Kids

When the war broke out in Israel in October 2023, it didn’t just delay Prof. Tzipi Horowitz-Kraus’s research — it completely transformed it.

The Technion associate professor and pediatric neuroscientist had set out to answer a deceptively simple question: what happens inside a child’s brain as they learn to read? But as schools shut down and daily life turned upside down, her study took on a new urgency — revealing how instability and stress can quietly alter a child’s ability to learn.

Using MRI scans, her team began tracking changes in typically developing children as they started first grade, a critical period in language and reading development. “Nobody has studied this in Hebrew-speaking children before,” she said. “We wanted to see how the brain organizes itself to support fluent reading — what changes, and when.”

The team had planned to start scanning on October 8, 2023 — the day after the war broke out.

“We couldn’t even begin,” Prof. Horowitz-Kraus said. “There was no school. There was chaos. And when the children finally started coming in a few weeks later, I noticed right away — something had changed.”

These six-year-olds were more distracted than the children she had scanned in previous studies. They struggled to focus. Something in their behavior had shifted. “Obviously, we realized that the environment and the situation affects the kids,” she said.

Rather than dismiss these effects as background noise, Prof. Horowitz-Kraus and her team began documenting them. They added a questionnaire to measure children’s exposure to war-related stress: sirens, disrupted routines, a parent called up to the reserves, moving homes, or just hearing frightening news on TV. Importantly, these were not children from the hardest-hit communities. “These are children living across Israel,” she said. “Not at the extreme edges. Just everyday Israeli kids.”

The changes were measurable — and meaningful.

Children exposed to higher levels of war-related disruption scored lower on cognitive assessments, including reading and language tasks. But even more striking were the changes in their brain scans. The MRI data showed less synchronization between key sensory networks — particularly auditory and visual regions essential for reading fluency.

“These networks are supposed to integrate — to communicate — as children learn to read,” Prof. Horowitz-Kraus explained. “But in the children exposed to more stress, that integration was weaker. And the more events they had experienced, the more disrupted those connections were.”

Her team now has scans from more than 80 children — 40 from before the war, and 40 during. The study has expanded far beyond its original question. But the core remains the same: how children’s brains support reading — and how that process is shaped by their environment.

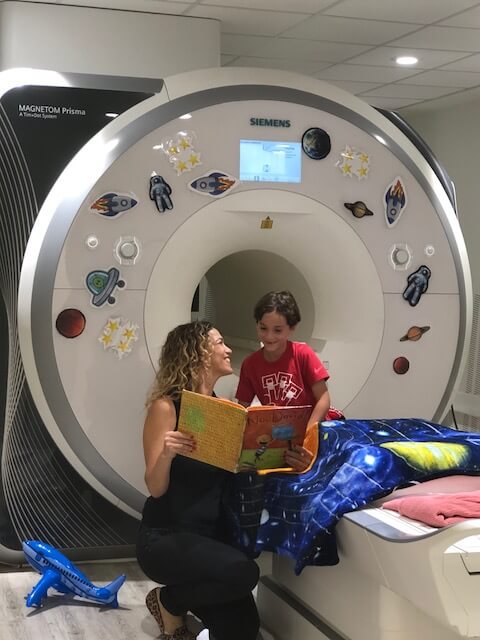

Prof. Horowitz-Kraus hopes the data will help inform not just science, but solutions. Her lab has already developed software tools that train children in reading fluency and cognitive control. She also points to dialogic reading — an interactive style of storytelling — as a low-tech, high-impact method to re-engage children’s cognitive networks.

“Dialogic reading activates the brain,” she said. “It keeps kids involved. It strengthens the systems we now see are affected.”

The ultimate goal is not just to describe the problem — it’s to address it.

“We’re not just talking about what happened this year. We’re talking about the future students of the Technion. The future engineers, physicians, and citizens of Israel. And we don’t yet know what the long-term effects of this disruption will be.”

Still, she remains hopeful. “Children’s brains are plastic,” Prof. Horowitz-Kraus said. “They’re adaptable. But they need the right support. And the more we understand how these systems work — and what throws them off — the better we can help them recover.”